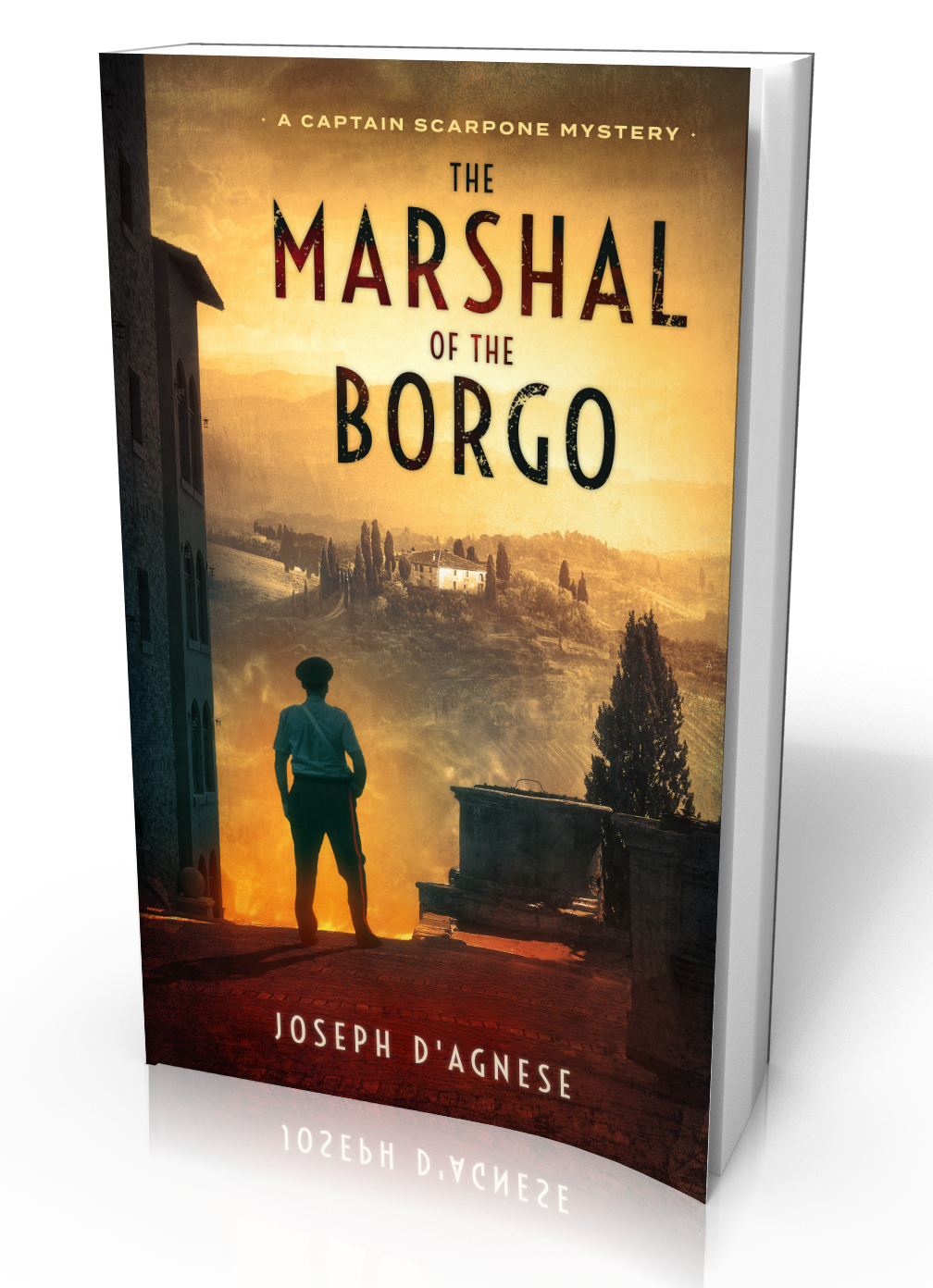

““…A tour de force of literary tone.””

Matteo Scarpone is a man more sinned against than sinning. Once a cool-headed logician and the pride of Rome’s carabinieri, he’s devastated when disaster rocks his world. He’s a lost man: Beaten. Shaken. HAUNTED.

Shunned as an embarrassment, he is exiled to a tiny village in the sticks—a hamlet, a burg, a borgo. But in this land of vineyards and olive groves, life is far from idyllic. Murder, witchcraft and hate taint the soil once tread by the Etruscans. Now the young captain must unravel a series of murders that pit him against a cynical evil and force him to use a power that he has long denied.

The Marshal of the Borgo follows in the tradition of Italian mysteries by Magdalen Nabb, Andrea Camilleri, and Donna Leon—but with a powerful twist.

Part whodunit, part ghost story, The Marshal of the Borgo makes for a very unusual paranormal mystery by a recent winner of the Derringer Award for Mystery Fiction.

Italian detective Matteo Scarpone first appeared in a short story in Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine.

PRAISE

“…A tour de force of literary tone.”—Lars Walker, author of the Erling Skjalgsson historical fantasies

BUY MARSHAL OF THE BORGO

“Joseph D’Agnese does it again.

On the surface, this novel is just a murder mystery.

But there is so much more just beneath the surface, and to mention it all would give too much away…”

Read an excerpt of The Marshal of the Borgo

Chapter 1

The dead man walked out of the bay trees at dawn. He was completely naked. Pink blotches covered his body. His eyes were dark and seemed to burn. He picked his way through the tall grass as if he were afraid of hurting his bare feet. I watched him carefully as he shambled through, and was privileged to observe the moment when he realized that he no longer had a sense of touch. He froze, and almost cried aloud. His face had the look of a child who has felt the splash of water for the first time.

He looked up and saw me sitting off a ways from him. Fear crossed his face: What’s happened to me?

I gave him a smile and waited. Before long he was moving again. He strode across the ground faster now, his feet, skin, and privates impervious to the assaults of the earth. He stepped out of the tall grass and stood there puzzling out his next move.

It’s not my way to give them any sort of hint in these moments. They usually figure it out for themselves.

The wind shifted, bending back the grass. He looked which way the wind blew and saw the house, the barn, and the rows of crops. He nodded at me and headed for the grapes. In a while he was gone. He had disappeared into the mist lying low over the vineyard.

I was alone again. I crouched low above the damp grass and waited for the day to begin. I could smell the dew and early rain. I could see the drops like crystals on the grass. But I could not feel them. Not the dew, not anything. This is my blessing, and my curse.

The earth is so still at these times of day. I have waited hours like this, waiting for you people to rouse yourselves. The earth never seems so beautiful, so still and fragile, as when you are not in it. These hours are bliss for me.

The door of the house opened and the woman came out. She kept her hands in the pockets of her apron as she walked, fearful of exposing her hands and part of her arms to the chill of the day. She walked briskly up the side of the hill outside her door, and stopped to take in the view. This was her morning routine, something she liked to do when her boy had not yet stirred from his bed.

She watched the fog, like me.

From where she stood, she could see the mountains to the east, and the great reservoir lake called Corbara, and the hectares of grapevines in distant fields. Normally the view strengthened her, but today she was preoccupied. Her brow had been wrinkled since she left the house. She dug in the apron and came up with a letter. For now, its contents are known only to her and to me. It was something about her mortgage resetting. It was not a large amount—another 89 euros—but each month, she’ll pay more to the bank and less to herself. It was enough to make her wonder yet again if this stubborn dream of hers was worth it.

She had dark eyes, clear olive skin, and long dark hair that spilled to her shoulders. Highborn and beautiful, she had had what most would call a fortunate life. She had traveled the world and returned to this village to make something of her father’s land. The parcel consisted of twenty-seven hectares filled mostly with grapes, a stand of olives, and, for the first time in her life, debt. It rankled her to be at the mercy of others, even an entity so impersonal as a bank in Orvieto.

A car door slammed. Startled, she stuffed the paper away.

Her workers milled around in front of their cars, nibbling on food they’ve brought. There was coffee, bread, cheese, and maybe even a bit of salty cured meat wrapped in foil. One or two of them caught sight of their padrona and waved. Buon giorno! For a moment, their voices carried easily from where they were, down by the road. But when they spoke to each other, she could not hear them precisely. Their voices reached her like the sounds of herd animals, eating and milling about and chattering to each other.

She turned her head and I could see her better.

I am drawn to this woman, my beautiful Lucia.

My purpose on this earth is somehow bound up in her, though I don’t know how or why.

I receive no instructions. No spoken word has sent me here.

I don’t know how long I’ve lived or where I’m from. Am I an angel or a demon? I honestly don’t know, for I’ve never met another of my kind. I know only that my Lucia needs me, and I must use what powers I possess to bring her happiness. But already this task seems doomed.

She scanned the line of trees between her property and the next. And just like that, she spied the birds. Eight or nine of them circled overhead in an unhurried yet determined configuration that can only mean one thing.

Lucia flinched.

I knew her thoughts: Her mind flew back to the day she witnessed something similar. She was just a child. A cow of one of her father’s tenants had wandered into a forbidden field and ate something green—she couldn’t remember just what—that made its stomach grow fat with gas and burst. They found the poor creature on its side, a kind of sickly, blood-tinged foam oozing from its wound while carrion birds wheeled in the sky, waiting. All the neighbors ended up buying the meat, as it could not be sold at market. It was tainted, though it still represented a calamitous loss for the family.

Lucia turned and screamed toward the house.

The door opened and out ran Magda, carrying Lucia’s son. The housekeeper ran up the hill, carrying the child. The two women spoke briefly, gesturing at the sky. Magda, it was decided, would go for help. Lucia would take the boy. Yes, come to Mamma, Leonardo.

At four or five years old, the boy was too old to be held by either woman. I have watched him for months now, and don’t care for him. He was a nice enough boy, just spoiled. Today he was dressed like a prince, and his chubby, delicate fingers played with a toy car. He was cranky because he’d been ripped from his breakfast.

Lucia rocked him while Magda ran down to the foreman, who was using a pocketknife to inefficiently carve a piece of bread on the roof of his battered Fiat. Magda, an unpretty woman with a nearly shaved head of black-and-white hair, has not spoken a word in fifty years. And so she gestured wildly. The foreman tried to comprehend. Yes. He understood. He was wanted on the hill.

He ran first to Lucia, then to the line of trees and brambles dividing the two properties. He dressed carefully each morning so that no one would mistake him for a migrant. And yet he failed. His face was sunbeaten, a look that marked him forever as a man of the fields.

I tried to read his thoughts but they were closed to me. I caught only his scent: unwashed smokiness cloaked in a light shirt and jacket. It would be hot here today but the morning was still cool.

He ran to find a way to cross the ravine between the two parcels of land. After a few minutes, he discovered that the trees and brambles were impassable. He was forced to run almost to the road and double back into the neighboring field. In a while, he made his discovery and called his mistress on his mobile phone. He was a poor man, but he carried a phone in his pocket every single day.

“Signora Lucia?”

“Yes? Tell me everything. What is it? A cow? Livestock?”

“No, Lucia, much worse.”

He spoke of his discovery, and uttered a single word.

Her heart leaped to her throat. She hung up without thanking him. Then she called the local police station, and repeated the word herself.

“Omicidio,” she said, panting, though she herself had not moved from her spot. “I want to report a murder.”

“An engaging story well told. That’s what Borgo offers—and what genre readers want.”