I can do it in three: boy meets ghoul. No, actually, it’s about Amy Armstrong, a pregnant New York City architect who inherits the ultimate restoration project, a 300-year-old farmhouse. She views the project and the rural town as a chance to start anew after a terrible assault. But there is some information about this inheritance, this property, and even the baby she’s carrying that the townspeople don’t want her to know. Something evil, and on a very grand scale. I may be over ten there. Can I borrow against 10-word descriptions of my future books?

In your promo copy, you tell people that if they like “The Lottery,” Rosemary’s Baby, The Shining, they’ll like your book. Who the hell are you to lump yourself in with literary giants such as Shirley Jackson, Ira Levin, and Uncle Stevie?

I didn’t do it; that was my publicist. I can’t compare my literary skills with those folks or anyone, that’s up to readers to see whatever connective tissue is apparent to them. Comparing types of story is something different, however, so I will say this about those comparisons, without giving too much away: Haven House puts a new twist on the moldy haunted house genre (à la The Shining), features a woman whose pregnancy sets horrible events in motion (à la Rosemary’s Baby), and has at its center the dark secret pact that binds together the people in an isolated town as well as the dreadful randomness of who that darkness impacts (à la “The Lottery”). So all I’m really saying is: if you dig chocolate, strawberry, and vanilla ice cream, I have a half-gallon of Neapolitan for you.

Hey—is it not a fact that you are like one degree of separation away from Ira Levin, and didn’t you go to his house for some holiday?

Yeah. The first professional novelist I ever met, so of course it’s not going to be some midlist-er I can wrap my mind around. It’s Ira freakin’ Levin. I had Thanksgiving with him, and after dinner he broke out those little explosive champagne bottle party favors. We shot them at the dining room chandelier. The thing was covered with streamers from years of previous holiday dinners and we added to it. Indoor fireworks! He made being a writer look fun, which I later realized was attributable to the fact that I saw him when he wasn’t writing. We used to drive to New York City to see Deathtrap on Broadway and then go backstage, walk around on the set. In fact, now that I think about it, the film I wrote and am producing this fall, The Suspect, owes some artistic debt to Deathtrap. Thanks, Ira.

In your novel, one poor wretch is quartered—his body literally torn apart into four pieces—and another is bisected. What have you got against whole people, or are you trying to teach some kind of sick lesson in fractions?

A haunted house novel where the house is in scattered ruins for the first half of the book could conceivably have the scares too delayed. I wanted to start by showing how high the stakes are in the town of Covenant Parish, and some of the horror is of the non-supernatural kind. Man’s cruelty.

You and your family live on a farm much like the demonic estate described in your novel. Does the countryside spook you for real? Are you, as Woody Allen says, “two with nature”?

When I first met my future wife, I had this little original Mac and I had taped a cancelled U.S. stamp right above the screen. It showed the state of Wyoming, a vast prairie. She asked me why and I told her it was my dream to be a full-time writer in a small town with a big rambling property. Be careful what you wish for.

In other horror novels, when someone buys or inherits a house, the house is already possessed. But in yours, the unwitting couple actually assembles the evil. Why’d you do it that way? What have you got against freestanding, wholly existing evil?

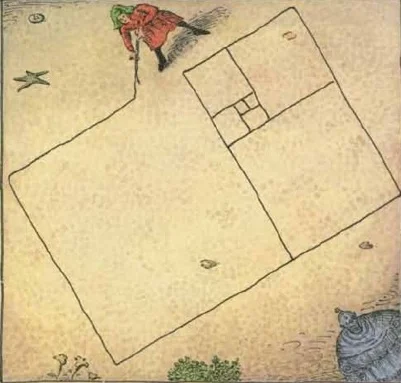

There’s always the-house-was-built-on-a-burial ground trope which has been, forgive me, done to death. And what I found so interesting about our place—Modoc Spring—is that they dug up the stones from the field, where they are worse than useless, and built a house out of them. Nothing goes to waste. The house and the ground beneath it are inseparable, and if the grounds are haunted, stacking these stones into some kind of order felt to me like a focusing effect. So my novel grew out of the observation that in every haunted house story, the house is already de facto in existence—and evil—long before the story starts. I thought, what if we came at it as a dismantled evil force that needed human hands to restore its power. You put in an architect with the dream of restoring a completely destroyed structure, and you’ve put the lightning rod in your protagonist’s hand.

You are a hybrid author in the sense that you are traditionally published and self-published. What do you think about self-publishing?

The short answer is that there were always two barriers to publishing: literary talent and printing. Traditional publishers said, “You get over the first hurdle and we’ll take care of the second.” The reason self-publishing traditionally had a bad reputation is that they said, “We’ll get you over the second hurdle for a price, and we don’t care about the first.” Mistake, because readers care about the first. Today the second hurdle doesn’t exist. There’s no barrier to entry. Anyone can and does publish. But that first hurdle is very real. Most self-publishing is terribly written. If a wannabe writer and a bookbinder don’t add up to a good book, neither does a wannabe writer and an internet connection. The publishers were right. Only by practicing and studying the craft can you become good enough to succeed in the market beyond friends and family. In my own case, at least having made it through the gauntlet of the New York publishing world in one piece tells me my writing is publishable. Now, how I get it to market is a matter of my own calculus. Is the publicity a publishing house can bring to a project worth more than, say, putting up free versions of some of my projects to attract those readers? I did just that with two stories from my shorts collection, "The Allnighter" and "Red Coyote Weekend," tons of them were downloaded, and from that number, a small but noticeable percentage took the leap of faith to buy the whole book, Confessions of a Velour-Shirted Man. The biggest problem I see in this market is that there is no New York Review of Books for self-pubbed book. Yet. That’ll put that first hurdle back where it belongs.

You were trained as a journalist and one of your more serious, nonfiction efforts was co-authoring a memoir of the “I Have a Dream” speech with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s attorney, Clarence B. Jones. How did you, a white guy, get inside the mind of a black, civil rights attorney?

I didn’t set out to be a historian, but it certainly is easier to move from that to fiction than to go in the other direction. Soledad O’Brien and Michael Bloomberg don’t tend to take the horror writer’s phone calls. To tell you the truth, the key to Clarence’s story wasn’t getting in the mindset of his racial background, it was understanding the underlying thematic of what he’s been through. He lived his life day-to-day and views it in that context. I saw the overarching picture and wrote to that. I picture him as the mythical ferryman, Charon. Or consider the weariness vampires have, outliving everyone around them (to bring it back to horror). That’s Clarence, and it’s not a race thing. We’re working together on another project called Uprising about his time as a negotiator at Attica during the prison takeover. Even though Dr. King has nothing to do with the story, many of the emotional elements to Behind The Dream are present in Uprising because Clarence is the same person in each circumstance.

I asked my father—who knows you well—if he had a question he’d like me to ask. His question inspired the title and indeed the tone of this post: “What the hell are you doing, scaring people?” How do you respond?

High-brow answer or low-brow? First of all, your father is fearless, as is anyone who can handle forty years of ridicule over his protective-plastic-covered living room furniture without breaking down. Forget confronting our fears as an essential part of coming to grips with our own mortality. Mankind is cursed with that, but it isn’t why I write horror. Rehearse your death on your own time. For me, the key is, they’re just words on a page. Nothing about it is real. But if you can make a grown-up disturbed enough, just by rearranging these same letters over and over again, then you are some kind of alchemist. If you can draw the chemicals of fear right into their bloodstream with words, make them leave the hall light on with your words, then you’ve gotten at the power of story. It is intoxicating.