For those who are interested in such things: A short work of mine is the featured Poem of the Week at The Five-Two, an online poetry weekly devoted to poems about crime. This offering is squeaky-clean and suitable for readers of any age. My thanks to editor Gerald So and reader Joe Paretta, whose reading of the poem (available on the site) imbue this piece with far more gravitas than I’d ever be able to muster. Thank you, gentlemen.

E.L. Doctorow (1931-2015)

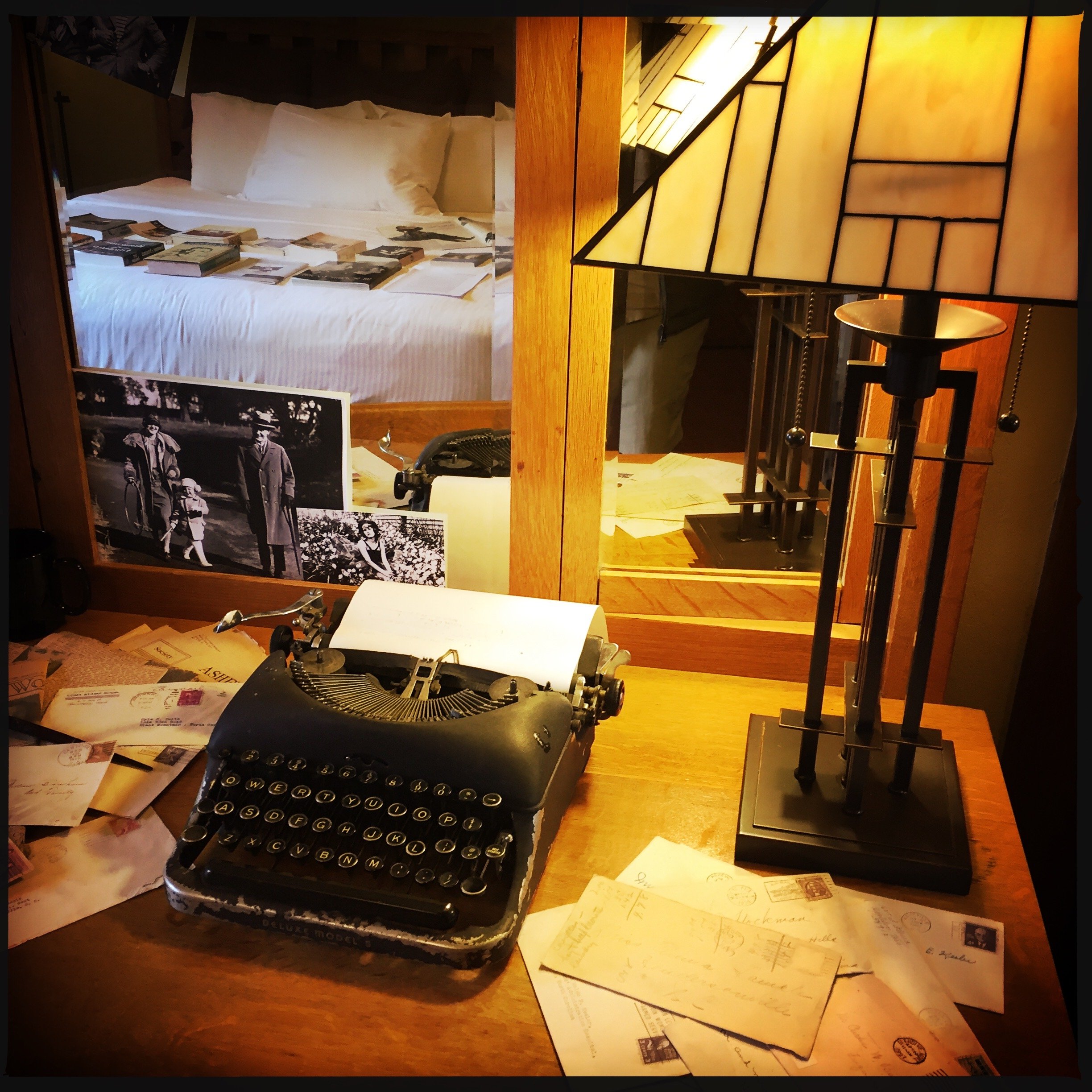

As I’ve mentioned in the past, I was (and still am) a huge fan of E.L. Doctorow. One of the first “adult” books I ever read was his. I picked up a paperback copy of Ragtime at a library book sale back when I was a kid, and was blown away—more by the novel’s narrative technique than by the story. Doctorow did things in that book that I didn’t know you could do in fiction. He eschewed quotation marks. He blended fictional characters with real-life figures doing fictional things. He presumed to speak as narrator for an entire period in history in a fearless manner.

I was never in love with history class at school, but I probably learned more about America and Americans by marching my way through Doctorow's bibliography. He was clearly fascinated with U.S. history, and how a writer could exploit and subvert the expectations of using historical material. In every book, you could almost feel him saying, “Yeah, I know this is supposed to be history, but it’s fiction first. Get out of the way—I’m writing here."

One of the best profiles of him I’ve ever read appeared in the New York Times Magazine back in 1985. You can read the whole thing here, but I’ve always liked this quote:

"Henry James has a parable about what writing is,'' Doctorow says. ''He posits a situation where a young woman who has led a sheltered life walks past an army barracks, and she hears a fragment of soldiers' conversation coming through a window. And she can, if she's a novelist, then go home and write a true novel about life in the army. You see the idea? The immense, penetrative power of the imagination and the intuition."

Helen. With the Heart.

Yesterday I woke to the terrible news that my cousin Helen had died in the night. She was 45. She leaves behind a loving husband and two children.

We grew up only eight miles apart and played often as kids. Then came an awkward adolescence where we didn’t see each other much. By the time we reconnected as adults, she was about to be married and move to New York City, where I was working. After all those years, we were delighted to discover how much we had in common—not the least of these was a love of writing.

Almost immediately, Helen was inviting me to dive bars in the East Village where she and others were reading their fiction. That was a side of her I’d never anticipated. She was an incredibly talented writer-performer. Even today I am in awe of anyone who can get up on stage and read something they’ve written. I don’t lean that way. Every now and then, one of the MCs would say by way of introduction, “Helen is an attorney, but hopes you won’t hold that against her."

Yeah—she was a lawyer. A tough one, who I suspect looked to language, reason, and intellect to bring clarity to chaos. In her fiction, young, smart women were always grappling with grim problems and stupidity in what should have been charmed lives.

We grew close in New York, Helen and I. Yesterday, as the shock set in, I relived that part of my life by rereading some of our old emails. In them, I saw us bitching about the city, about coworkers, about the madness of our families, her ex-boyfriends and my then-messy stream of girlfriends. I remembered how, while living in Brooklyn, New York, Helen had used her training to solve some nagging mysteries about our grandparents, and in the process uncovered some new ones. Her emails were often addressed, “Hey, Cuz,” and signed, “Love, Me.” When I moved to Italy for a while to be with Denise, Helen would sometimes phone my old U.S. mobile number and leave long voicemails filling me in on her life.

Hers was a sweet one that had become unaccountably burdened by that chaos, after all. Somehow she developed a heart problem that could only be resolved by a transplant. She was in a hospital bed for nearly three months while an BiVAD machine kept her body alive. Two months into her stay, a doctor friend broke the news to me and another cousin: “Her body is in complete organ failure. It would be a miracle if she survived."

She got that miracle. As some other family in the universe mourned the loss of a daughter, Helen got her life back. She was 33 years old. She retired from the law and focused on being a mom instead. Initially shy about talking about her experience, in time she took to the road, speaking at high schools and blood drives about the importance of being an organ donor.

“Why do you do this?” people would sometimes ask. "Tell people your life’s story?"

“For two reasons,” she’d say. “One day you may be in a position to help someone like me. Or one day you might be me.”

Fifty percent of heart transplant recipients live only ten years. If you’re a seventy-five-year-old heart transplantee who lives only a decade more, no one feels as if you’ve been cheated out of a long life. But yesterday I was feeling cheated, even though all of us—especially her husband Tim and her kids—were privileged to have thirteen more years with Helen.

Her doctors had hoped to help her, but that miracle heart of hers gave out suddenly, ending the life of a woman who was the closest thing to a sister I’ll ever have.