I wrote this tiny piece back in 2001 for a national food magazine. They paid me for it, but never ran it. No idea why. No explanation why. Freelance journalism is known for this sort of fickle behavior. Editors love things, then hate them. This article was deliberately short, intended for the magazine’s front-of-the-book section. It was supposed to run with a recipe that I provided. The article has never seen the light of day—until now. I’ll offer some current thoughts on the piece at the end. But first, the story.

I remember Nonna.

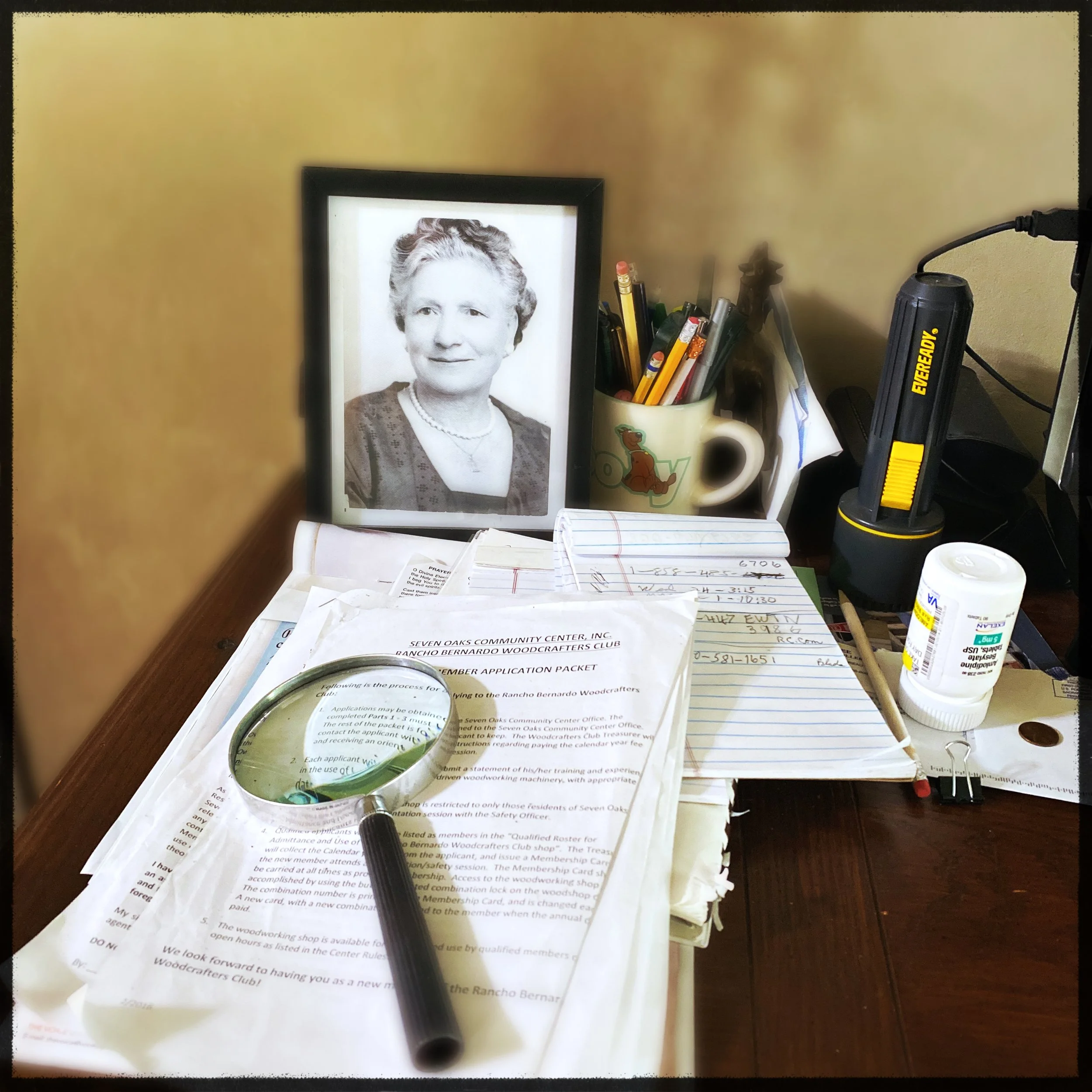

Every year as the holidays drew near, my grandmother Concetta would whip up batches of a confection she remembered fondly from her Neapolitan childhood, when she worked in a little restaurant. Nonna fried tiny dough balls until they were golden pellets, and folded them into a pot of boiling honey. They came to the table in a glistening mound, decorated with sugar sprinkles. My brothers and I broke off pieces with our fingers and popped them into our mouths like popcorn. This became our hearts’ desire as kids: honey balls, or struffoli.

Strictly speaking, struffoli (pronounced STROO-foh-lee) are a southern Italian treat, most likely a peasant way of making something cheap—fried bread and honey—look and taste like something pricey: candy or nuts. Today Italian bakers toss them with candied fruit, slivered almonds, and pine nuts to reinforce (or knowingly mock) the illusion. Others add orange and lemon zest to the dough before frying to impart those flavors to the final dish. In Italy struffoli are eaten usually at Christmas or other feast days, but my brothers and I, American kids, never cared what the calendar said. Anytime Nonna visited, we demanded struffoli. When a visit wasn’t imminent, we pressed our mom into making them herself.

My mom’s handwritten struffoli recipe card, later amended.

There was just one problem: Concetta wouldn’t cough up the recipe—and never did, even when she passed away at age 95. My mother, who is Italian-born and no slouch in the kitchen, did the best she could mimicking her mother-in-law’s recipe, while my father sniggered on the sidelines, saying thing like:

“These are good, but they’re not like Concetta’s.”

“Nobody makes these like Concetta.”

“Mmmm—these are…okay.”

It’s a wonder the man didn’t get his face fried in hot oil.

These days I spot struffoli in Italian-American bakeries year-round, the balls always larger and tougher to chew than I’d like. I even spied Carmela Soprano, that high-end gangster’s moll, sneaking a few out of season on HBO’s The Sopranos. That did it. I asked nicely if my mother would show me how to make them. She agreed, but only after delegating the most tedious part of the process to me.

“Okay, but you’re rolling them,” she said, going for the flour.

A few hundred balls later, I knew why they are a once-a-year treat.

Which is why I think this would be a fun treat to make with kids. Assuming parents did the frying, kids could do almost all the other tasks: making the dough, shaping it into long strips, breaking them into tiny pieces, rolling the balls, and mixing them in the warmed honey. It’s a recipe that can be time-consuming, unless you had lots of little hands to help with rolling of the dough balls. The presentation is lovely: they come to the table looking like a golden beehive.

Over the years Mom has slowly refined her recipe, and I’m happy to report that my parents have reached a struffoli détente. Her struffoli are light and sweet, and when my father nibbles them, nothing more than “Mmmmmm” escapes his lips.

“Well, isn’t that progress?” I asked my mother.

“He knows mine are better,” she told me under her breath, “He just won’t admit it, the bastard.”

***

Cute piece, right? The thing that strikes me now, 22 years later, is that Nonna, Mom and Dad are all gone. The recipe I managed to cajole out of my mother still lives on my hard drive, and I will attempt to make it this Christmas, and tuck the recipe into a family cookbook I’m working on with one of my brothers. So it wasn’t a complete loss of time and energy, and I’m grateful that the article forced me to collect my mother’s recipe. That said, I still wonder why the magazine didn’t run the piece. Was it too anecdotal, too vulgar, too Jersey? I know it doesn’t go into tremendous depth on the history of the dish, but they did contract an article that was only 400 words in length. That’s painfully short. Either way, I’ll never know, and don’t much care. One thing I do feel bad about is that I never thought to photograph my Nonna or mother’s dishes. Those plates were a thing of beauty, but now they live only in my memory. The photo that appears at the top of this post joins us direct from Wikipedia.