I have racked my brains over the years trying to recall exactly which puppets he brought to our class. I feel like one was called Hairy or Harry, but I can’t know for sure. (I do know that it was a Muppet. The character had that cuddly fabric look all us kids knew from watching Sesame Street in the early ‘70s.) What is less hazy in my memory is how Hunt made each of those characters come to life with a few simple gestures—head shakes, hand movements, a certain twist of the mouth, and Hunt’s own voice. It was magic of the highest order.

The next time I met Hunt he was performing at a friend’s birthday party in our town. Apparently he’d earned money for years doing kid’s parties. And then, one day, while on a visit to New York City, he phoned Henson’s office from a payphone and asked if they could use a puppeteer. As luck would have it, auditions had just opened. One visit to the studio and he was in.

I remember how excited I was to watch The Frog Prince when it aired on TV. It was Hunt’s second Muppet special. Shortly after, he performed in another special, The Muppet Musicians of Bremen. Mrs. Stampa told us all to watch, and we did.

For decades, long after my puppet obsession waned, whenever I watched a Muppet movie or TV show, I’d always scan the credits, waiting for the name of “our” Muppeteer—Richard Hunt, the local boy made good—to appear on screen. I was never disappointed. Hunt’s career with the Muppets was lustrous; he breathed life in so many of the characters we all know and love, like Scooter, Janice, Beaker, Statler, Sweetums, and many others.

And then one day his name disappeared from those credits. Richard Hunt died in 1992 at age 40 from complications related to the HIV/AIDS virus. I don’t think I learned of his passing until many years later, when I saw his name mentioned in a playbill by TOSOS, New York City’s oldest LBGTQ+ theater company. Someone had mounted a tribute to Hunt, who was openly gay.

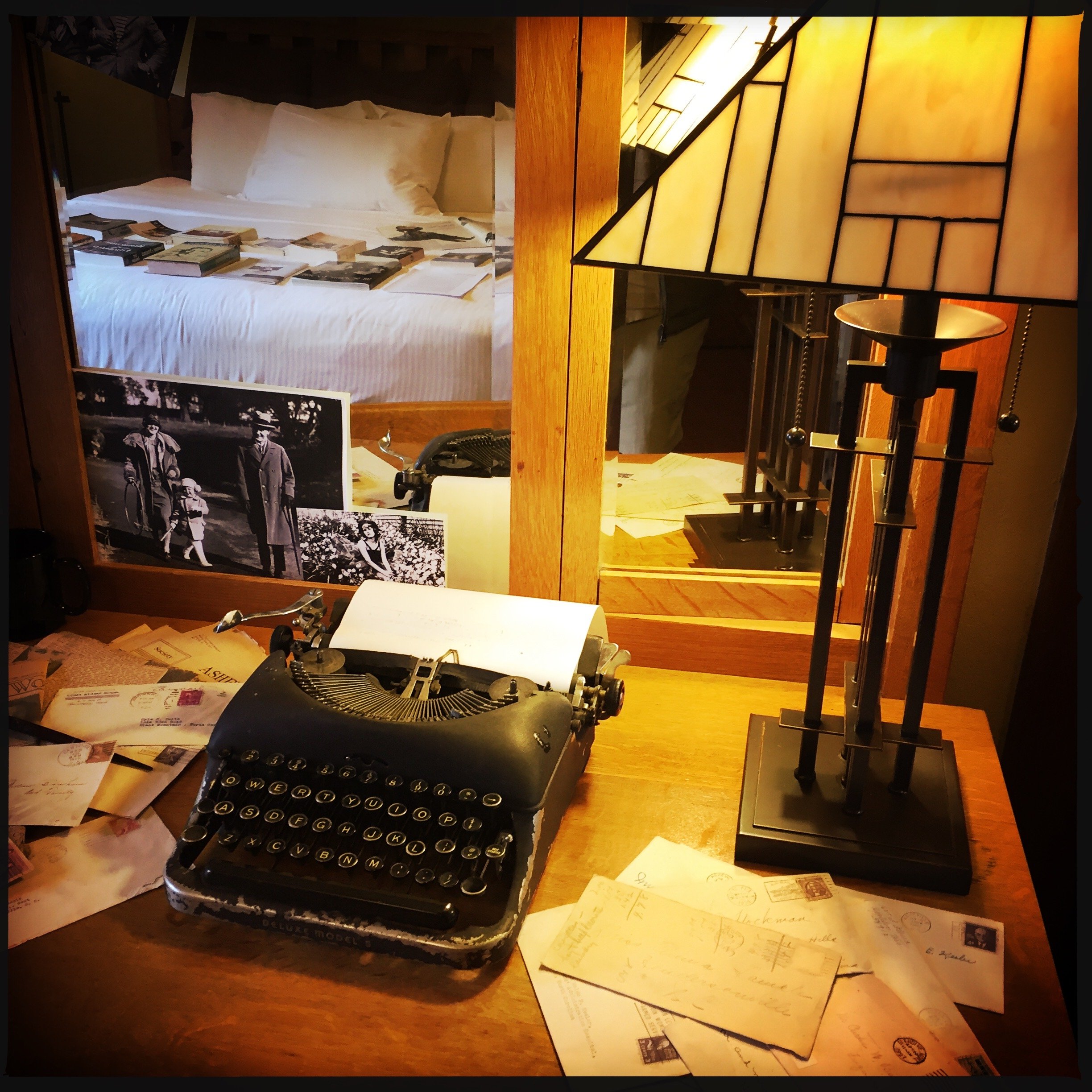

I had to basically wait until the Internet was a thing before I could easily learn more about his life and career. Only then did I learn that Hunt had more than 60 credits to his name on IMDB. And that his memory was being kept alive by legions of puppetry and Muppet fans in articles such as the ones found here, here and here. By far the richest vein on Hunt’s work comes from the pen of Jessica Max Stein, who is currently at work on a Hunt biography. She’s posted excerpts of the work in progress on her website, and shared interviews with Richard’s Mom, and posted other pieces here and here. I also found a sweet remembrance by Hunt’s work colleague, Kermit the Frog, that brought a smile to my face.

That’s the beautiful thing about puppets, Muppets in particular. They are eternal. They enter our lives when we're young and impressionable, and never quite leave, though the people who brought them to life—Henson, Hunt, among so many others—may have left us. Until Hunt's biography is published, I’ll content myself with stories like these, and the memories of the day I learned it was okay to be puppet crazy.