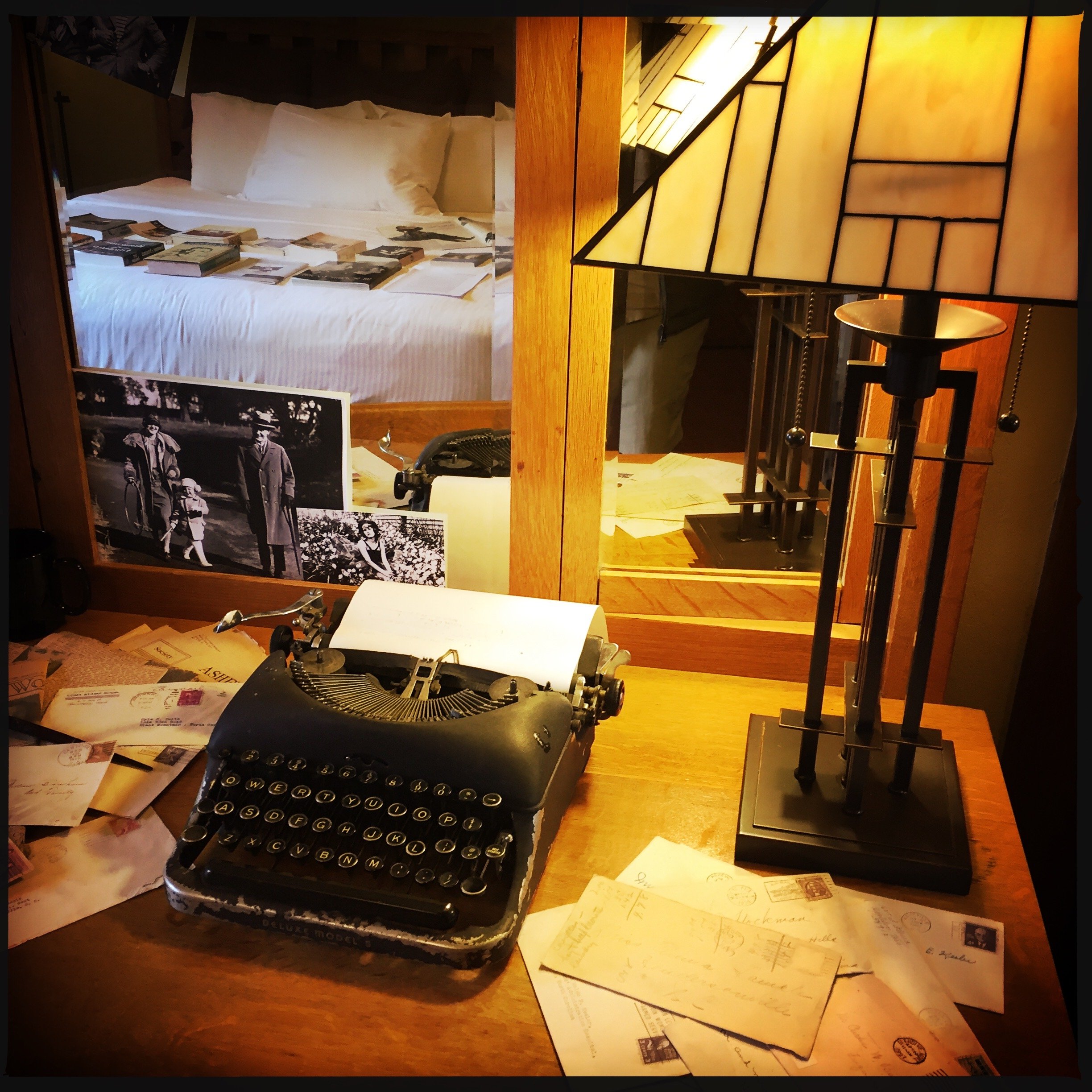

My late journalism professor John C. Keats came from the school of hard-hitting newspapermen of the 1940s and 50s. Later in life he switched to magazine work, which was more lucrative. In one story he told, a publication paid his way from Philadelphia to New York so that he could be on the premises while they edited his work. They were in a rush to get the article edited so those pages could be shipped to the printer. They put him in a nice office with a typewriter, where he worked on other projects while waiting to be summoned. He enjoyed fine lunches and a lovely hotel room at their expense. Finally, after a week, an anxious editor brought in some sheets of paper with some redline comments. "Here it is! We're going to need this right away. When do you think you could get it to us?"

"You can have it in fifteen minutes if you get out and shut the door," Keats said. He was always a little cantankerous. (Read more about him here.)

His editors were under the impression that their edits would require a lot of time to work through. So much time that they imported the writer and installed him close to their offices for one expensive week.

Nothing has changed in 50 years. One thing that hasn't changed is that the person who actually does the work—let’s call that person the freelancer—must adhere to the deadlines, while deadlines for the freelancer’s clients are infinitely more elastic. But that’s another story.

What I really want to talk about is how people equate time with quality. If a book takes a long time to produce, people reason that it must be better than a book that took a short time to produce. A fast writer is judged harshly under this paradigm.

I do a lot of ghostwriting. I wrote a memoir for one client that changed the way people saw him. He gained new fans. His diehard fans loved him even more. All because the book showed his human side. It showed how he came up in the business world by guts and brains alone. Prior to this, the prevailing internet narrative held that he’d inherited a ton of money, or had been handed his career by successful relatives, which wasn’t true at all. Yet the whole time I was researching the book, he fought me on this, afraid to reveal his real story and his vulnerability. But I finally managed to wrench it out of him. The book’s emotionality is what people praise about it to this day.

Our interviews took several months to complete. But in the end, that book took me 14 days to write. (I have a couple of posts coming that talk about this project.)

My wife went through something similar on another ghost project. By the time the editors hired my wife, the book was already in danger of becoming a “problem” in the minds of the editors and the publishing house. The previous writer had walked, nothing had been written, and the deadline was looming fast. On a conference call, my wife announced that meeting a deadline only two months away was reasonable and achievable. The “author” expressed concern: “That’s too soon. This needs to be good.”

The implication: Shouldn't this process take years?

Another book, one of our own that I wrote with Denise, went on to sell 100,000 copies. It was our first big book. People began inviting us to come speak to their groups because of it. At those events, someone would inevitably ask how long it took us to write that book. It’s the sort of thing people always ask writers.

“Five years,” I’d say, telling them what they wanted to hear.

Actually, it took us a month. Not that we wanted it to; it just happened that way. We were really organized, and devoted to the process.

So we’ve been through this a lot. People don’t want to accept that a good first draft of a book can be written in such a short amount of time. If it can, goes the thinking, it can't possibly be any good.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I don’t love to write a book that fast. I actually think it’s nice to have a generous amount of time to write a project, take a break from it, then revise it carefully, digitally and on paper. But I don’t always have the luxury of time, because of deadlines and other commitments.

But it is possible to write fast and well. I have one friend who for a while adhered to an insane production schedule, writing a novel a month. He didn’t love doing it, but he could do it. And he did it because that’s what he had to do—at that moment in time—to pay his bills.

I’m sure that there are musicians who’ve written hit songs in days, hours, or even minutes. Stallone wrote the first Rocky script in three and a half days. I know local artists who crank out great examples of their work in days so they’ll have a good inventory to sell at arts festivals at the end of the month. I know designers who do the same thing. They just keep churning the work out, and you can’t tell that they did it in such a short amount of time. All these people do what they do because they’ve attained a certain level of mastery. In the words of another co-writing client of mine, they’re experts.

I took a lot of art classes when I was a kid. I remember one instructor telling me to stop making sloppy circles on my page as a way of warming up, and learn how to put down one correct line instead.

Watch Picasso draw that bull in thirty seconds. Look at how he knows just how to move his hand to create the slope of the bull’s back. When he flicks the brush at the bull’s head, he knows from years of experience that the bristles will leave a stroke suggestive of the bull’s horn. And he knows just how little paint to apply to hint at the bull’s legs.

It's not the time but the talent of the artist that matters. Experts do a lot with the time handed them.