A lot of writers are talking this week about Hugh Howey's AuthorEarnings.com website, which analyzes some data drawn from Amazon to make some interesting observations about the traditionally published versus the self-published world. Another component of the website is a questionnaire asking writers what they earn. I think it will yield some more cool data, the more authors plug in their info.

This comes on the heels of a recent survey conducted by Digital Book World, which found that most authors earn less than $1,000 a year.

Both studies have their supporters and detractors. Both are shaping up to be controversial in their own ways. I’ve been thinking about releasing some of my own figures for a while now. I’m going to try to do that in this post.

It’s just a little tricky. I daresay the authors debating this stuff right now are predominantly fiction writers, whereas I’m a predominantly nonfiction writer with a background in journalism. Complicating the issue is that a lot of my books were ghostwritten for other people. In other words, I acted as the “Writer” for a more prominent “Author.” In fact, that’s exactly how the two parties are usually designated in the collaboration contracts. I’m the Writer. Some other person is the Author.

Nearly all of these contracts contain confidentiality agreements, so I’m not really at liberty to spell out who I wrote those books for, the money I was paid, what those books were about. So I’m going to be a little coy. But I’m going to try my best to give you the figures because I think they make an interesting counterpoint to what fiction authors are paid. Suffice to say, I’ve been earning more than $1,000 a year, but I’m writing a mix of my nonfiction books and other people’s books. And some of these deals mean that I am entitled to a share of those authors’ earnings for the life of the book.

Bear in mind that I’ve been supporting myself as a freelance writer—writing newspaper and magazine articles, and books—since about 1997. Since about 2006, a large chunk of my income has come from writing books. The last two proposals I wrote earned the Author and me a gross advance of $100,000 or more. This in a time when advances are at an historical low. In some cases, I wrote these proposals and books alone or with my wife. While I think I’ve grown into a good proposal writer, I can’t ignore the fact that the Author’s platform, brand, prominence, and story almost always accounts for the size of the advance. That said, traditional publishers feel more confident about offering sizable advances when they love the proposal. It’s my job to make them fall in love with the Author’s story.

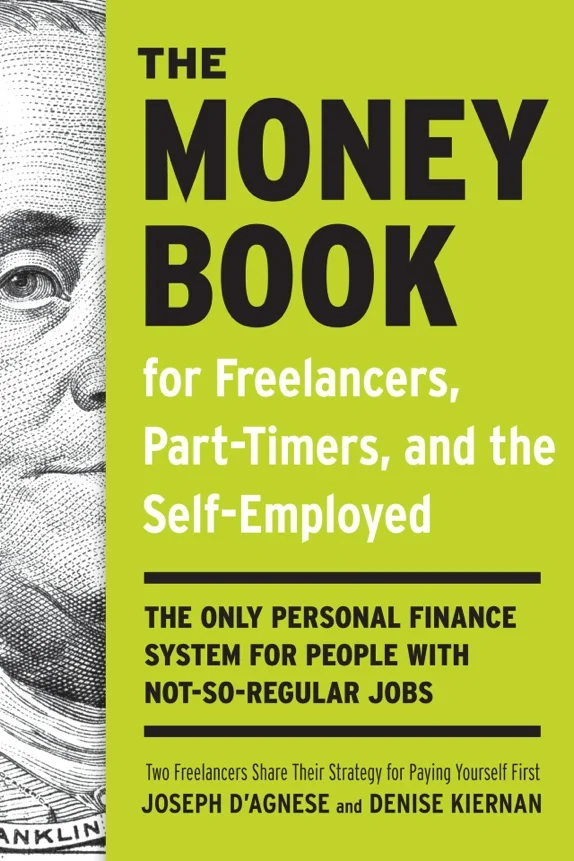

I have omitted the details of my wife Denise Kiernan’s bestselling book from this list. These are only books I have been a party to. The list is a mix of my own books, ghosting gigs (where I wrote the proposal that sold the book and received both a percentage of the royalties and advance), and work-for-hire projects where I just wrote the book for a flat fee.

Sometimes I wrote the proposal but the book didn’t sell and the Author stiffed me on the proposal fee. Many times I spend hours on the phone conferencing with a potential Author, only to have the project dry up and blow away. It’s just the nature of the business.

The clock on these books starts in 2002 and ends in 2014, with a ghost gig I’m about to undertake…

GHOST GIGS

* My first ghost gig: 2002. Big 5; work-for-hire, $25,000 flat fee, no royalties. Editor: “It’ll only take 5 months, tops.” It takes a year, and the demands on my time costs me lots of other freelance work.

* Sports book ghost gig: Sold via proposal. Big 5; 40% of advance and royalties. Our share to write book: $62,000.

* Nonfiction ghost gig: Sold via proposal. Big 5. 50% split of advance and royalties with Author. My share to write book: $50,000.

* Health book ghost gig: $5,000 to write the proposal for a book already written by the Author. No advance or royalties.

* Business book ghost gig: About to be sold via proposal. $10,000 proposal fee. Big 5. 40% share of advance/royalties; 42.5% if my proposal lands a deal in excess of $150,000. Guaranteed minimum: $40,000 to write book.

WORK-FOR-HIRE

* Adult nonfiction book: $3,000 advance, token (2%) royalties.

* Adult nonfiction book: $25,000 flat rate, no royalties.

* Adult nonfiction book: $50,000 flat rate, no royalties. Client: “This will take a few months.” It takes three years.

* Adult nonfiction book: $10,000 flat rate, no royalties.

* Adult nonfiction book: $7,500 advance, token (1%) royalties.

* Hollywood book gig: Big 5. $12,000 to write book. No royalties.

* Adult nonfiction museum book: Work-for-hire. $15,000 flat rate, no royalties.

* Nonfiction business book: $12,000 flat rate, no royalties.

"MY" BOOKS

* Kids’ book 1: Proposal. Advance of $2,250 each, to myself and a my co-author, with a standard paperback royalties split between both of us.

* Kids’ book 2: Sold on the basis of a proposal and a finished book. Big 5; $5,000 advance for me, standard hardcover royalties (5% and 5%) split with illustrator.

* Adult nonfiction book: Sold via proposal. Big 5; $40,000 advance, standard paperback royalties.

* Adult nonfiction book: Sold via proposal. $10,000 advance, standard hardcover royalties.

* Adult nonfiction book: Sold via proposal. $12,000 advance, standard hardcover royalties.

CONCLUSIONS

Actually, I’m not sure what conclusions you can draw from all this. In general, having gone through the fiction submission process, the advances on work-for-hire and ghost gigs tend to yield better advances, which is why I keep doing them.

Publishers tend to be willing to part with more money when they think the Author has a name or brand that will propel them into the media, or they think the subject is unusually compelling. That’s why some of these are in the mid-five figures. These figures also reflect my gross; subtract 15% agenting fees from all these figures. These payments were also paid in halves, thirds, and fourths. For at least three of these books, we have not yet received final payments because the paperback has not yet been published.

Would I like to be writing my own fiction? Sure, but in the same way that a lot of fiction writers have day jobs, my day job is writing books for other people.

For more on what ghostwriting entails, I’d refer you to this interview with agent Madeleine Morel. I have met Ms. Morel, a ghostwriting specialist, but she is not my agent.