I majored in journalism in college and a lot of my friends from those days eventually left that profession for theoretically greener pastures. One went to work building websites for B&N. Another became the spokesman of his local power company. Still another became the principal of an elementary school. A while back, I came to realization that there were only a few of us in the old gang who still wrote for a living. That says more about journalism than my friends, I suspect. You go where you must to support yourself and your family.

was one of the people I knew back then who stayed in the traditional world of writing. We first met in a creative writing class in the mid-eighties, but would also see each other at the journalism school across the street. She, like me, seemed destined for both worlds—creative writing and journalism. Her mind and her work always impressed me, and it still does.

Today she’s a teacher and practitioner of narrative nonfiction. She uses the dramatic techniques of fiction to write about the real world. In 2010, she published

, a book about a 1943 coal mining disaster in Montana that snuffed out the lives of more than seventy men. Kush’s voice is on every page, paying tribute to men she never knew and their families.

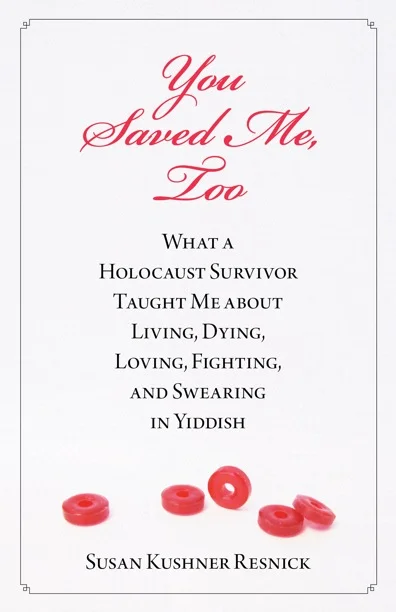

This month Globe Pequot Press released her third book,

. It’s a memoir of the friendship that sprung up between Sue, then a young Jewish mom who was struggling with depression, and a 76-year-old Auschwitz survivor, Aron Lieb, whom she met at a community center.

The two are drawn together by their Jewishness, their quick wit, their charming personalities. Though they are separated by four decades in age, they form a connection that will ultimately sustain and nurture both of them. Sue becomes determined to help Aron have a good life and death.

Her voice is key to this book. Here she is talking about the day she officially because Aron’s health care proxy.

After we signed next to the X’s, I dropped you back at your apartment. Later, I told a friend what I’d done.

"Now you have three aging parents to take care of," she said.

Put that way, the new arrangement sounded like a burden, but I wasn’t worried. I owed you whatever you needed because you had given me something no one else ever had: a character test. Or, rather, God has given me a test in the form of you. Here comes an old man walking toward you and your baby. Will you smile and walk away? Or will you stand and talk, bring him home, put him on your heart? Will you tell the story that his little sisters didn’t live to tell, and someday ask your children to keep his memories pulsing? Will you embrace the task or ignore it? This is your test.

I hope I will pass.

It’s a very moving book, but a funny one too. Actually, kind of hilarious. And it’s gotten starred reviews and rave reviews from authors and the

New York Journal of Books

. Sue agreed to answer some of the questions I had after I digested the book.

How did your relationship with Aron morph from him possibly being a subject for an article you were writing into a book. At what point did you make the shift?

It wasn’t an abrupt shift because we started as friends, then I realized he might be story-worthy, which I think may have been an excuse to keep hanging out with him. Once a book proposal about him and his girlfriend was rejected by many publishers, I packed up the little cassette tapes and the steno notebooks that contained his life story. Then we were back to being just friends and our relationship got deeper and more complicated because he needed help navigating the medical system. I wasn’t officially reporting on him during those years, but I always suspected I’d go back to writing about him someday, when I figured out the story, so I kept taking notes whenever he said something interesting or hilarious.

That makes sense. The book feels remarkably “reported” in the sense that you’re recalling things from the early days of your 14-year friendship.

That’s the beauty of memoir —you can chronicle life as you live it. And he’d ask me how the book was coming along every once in a while. I’d say, ‘I don’t know what to say about you.’ It wasn’t until his dying day that I figured out the story I needed to tell.

And what was that, the voice? Every review I’ve read talks about how the book is written in the second person. That’s not a narrative mode that’s used very often.

I realized as I was driving to his deathbed that I was talking to him in my head. I knew he was unconscious, but I was telling him to wait for me. I’d always promised him that I wouldn’t let him die alone. At that point, I wasn’t sure he was dying, but just in case, I wanted him to know that I was holding up my end of the bargain. And he had to hold up his: no dying until I arrived. Once I had that conversation started in my head, the rest fell into place. The biggest challenge was giving the reader information about the past while staying in the conversation. Fortunately, Aron was 91, so I could write “remember when” a lot.

At one point in the book you assert that you and Aron are soulmates—a word normally used to describe a romantic connection with someone. How can a happily married woman, a mom, claim to be a soulmate with a man who is forty-four years her senior and to whom she’s not related to by marriage or blood?

When we met, I was 32 and he was 76. I know most people think of soulmates as romantic partners, but I prefer the definition of soulmates as two halves of one person. That dynamic could be dangerous in a romantic relationship.

Not a question, just a wow: I loved how you managed to convey history—American history, WWII history, etc.—without making us feel like we were reading history. Well played, ma’am, indeed.

Thank you so much! The story brewed for 15 years. I’m glad the end result goes down easy.