Today is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s birthday. So please, for the love of God, read The Great Gatsby or one of his short stories. Or something.

This past weekend, I went to visit the Grove Park Inn, a historic lodge in the town where I live. Every year on Fitzgerald’s birthday, the inn opens the suite of rooms the writer rented often when he was in town.

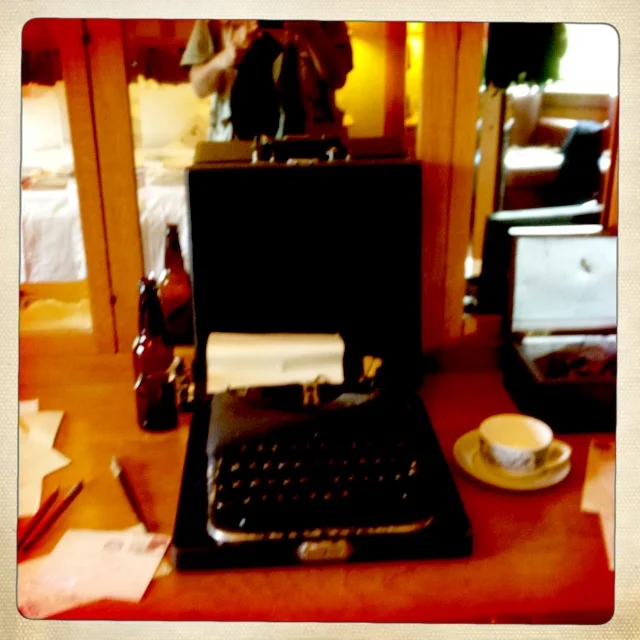

Truth be told, the story of the Fitzgeralds and Asheville, North Carolina, is an overwhelmingly sad one. Fitzgerald was in town visiting his wife Zelda, who was committed to a sanitarium in town. On these birthday weekends, the lodge decorates the room with the accoutrements of drunkards—beer bottles and the like, and a local literature professor greets tourists and shares some of the Fitzgeralds’ story. (Denise took some footage of our talk with Prof. Brian Railsback, and I hope to post some clips one of the days.) Among one of things we learned was that when Fitzgerald elected to stay off gin, he switched to beer, drinking as many as 35 cans or bottles a day.

Zelda Fitzgerald suffered her first breakdown in 1930, and by the time the couple arrived in Asheville in summer 1935, Fitzgerald was trying desperately to support her medical stays by writing commercial short stories. By the second summer, 1936, Fitzgerald had pubished his now oft-anthologized essay The Crack-Up, his mother had died, and his inheritance was keeping them afloat.

Grove Park Inn legend has it that he flirted with countless women while here, checking them out as they entered the hotel from the window you see here. He had at least one embarrassing, documented affair.

Fitzgerald famously gave an embarrassing interview to a New York Post reporter while in these rooms. The interview, found here, reveals him to be a hopeless alcoholic.

Fitzgerald died of cardiac arrest at the age of 44. Zelda outlived him, returning to Asheville, checking herself in and out of the sanitarium on Zillicoa Street. Some local scholars say she finally found peace here in the mountains. (They infer this from her paintings.) If so, the peace was short-lived. One night in 1948, as Zelda was locked in her room awaiting electroshock therapy, a fire broke out. She and eight other women were killed. She was 47.

The hospital grounds are in my neighborhood. Tour buses roll past there all the time, filling tourists’ heads with the inevitable claim of ghost sightings.

If you walk there you can find a little stone to Zelda’s memory, and this quote: “I don’t need anything except hope, which I can’t find by looking backwards or forwards, so I suppose the thing is to shut my eyes.”