It’s Nobel Prize season. I spotted this article on Slate the other day that listed potential women candidates for the Nobel Prize in Physics. (No woman has won that award in fifty years, and surprise—one did not win on Tuesday.)

One of the women cited in the article is the American astronomer, Vera Rubin, now aged 86, who is known for her work on dark matter and galaxy rotation.

Ages ago, I interviewed Dr. Rubin briefly for an article I was doing on the three scientists—Gamow, Alpher, Herman—who worked on the Big Bang theory (the actual scientific theory, not, ahem, the TV show). Many in the community felt that they had been slighted because, although the trio won numerous awards in their lives, they never won the Nobel. An award was actually later given to the radio astronomers who confirmed the Big Bang.

The story I wrote was really about how one scientist in particular dealt with that snub and perceived others throughout his career. I’ll never forget my talk with Dr. Rubin because she was willing to speak frankly about something scientists rarely discuss: emotions. From the text:

Alpher and Herman’s story raises interesting issues about the personal side of science. Yes, all human beings have feelings. Yes, every person is allowed to reach their boiling point. Scientists just happen to belong to a profession where you are not allowed to show it.

“It was a horrible injustice but I don’t know what you do in such a circumstance,” says Vera Rubin, a friend to both the Alpher and Herman families, and an astronomer who received the National Medal of Science in 1993. “It would have been nice if they had had happier lives. They could have known that they did something very valuable, and they could have been happy with this. I think perhaps injustices are in the eye of the beholder, unfortunately.” And then she says, “There’s no doubt that they could have been and should have been treated nicer by the [Nobel] committee. They really do have a legitimate complaint, but they could have responded a little differently… They had not gotten the recognition they deserved, but if their personalities had been different, they could have been happy with the knowledge of this great thing they had figured out. And they perhaps could have even been treated better by the committee if they had not just been so obviously angry.”

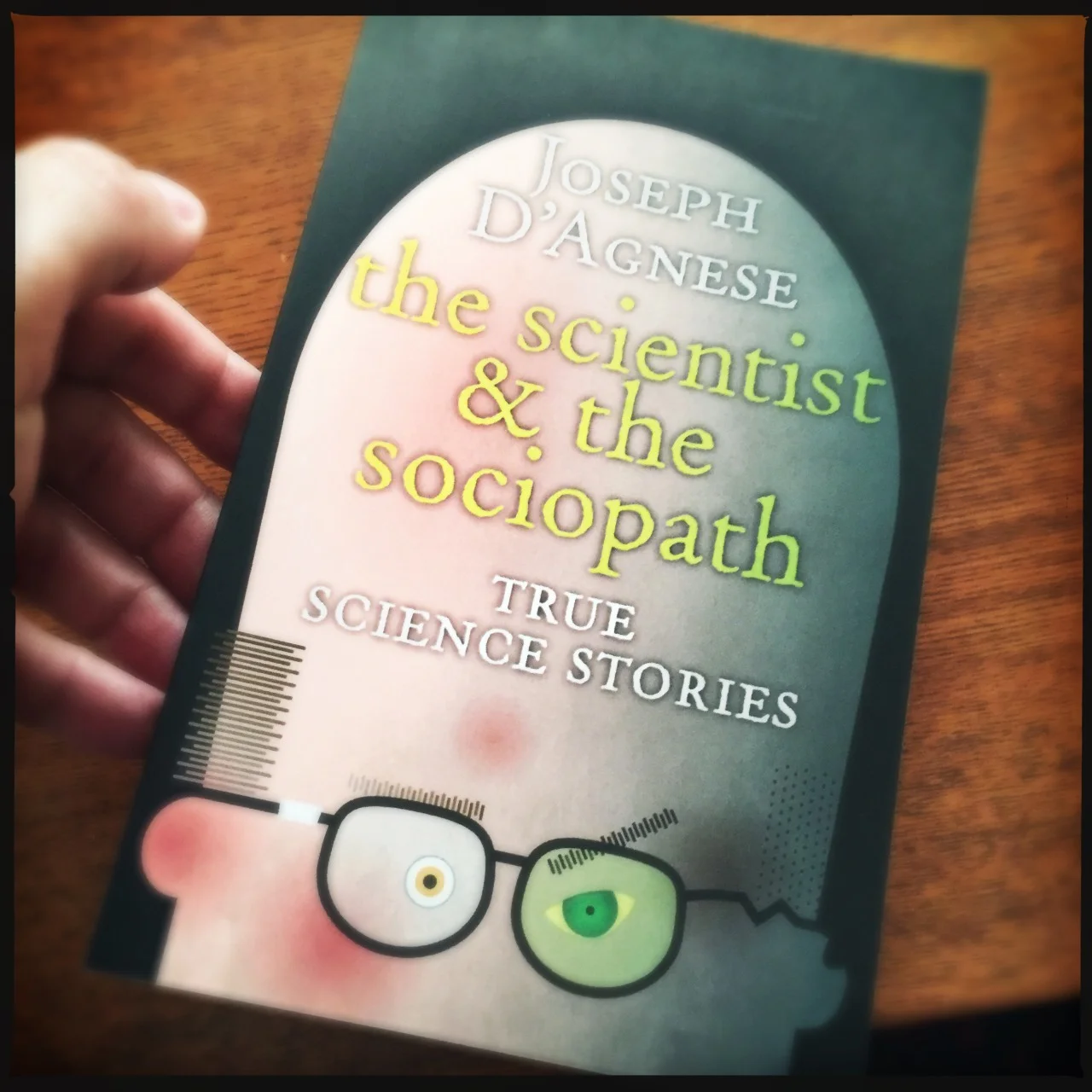

You’ll find that article and others in my nonfiction book, The Scientist and the Sociopath, which is finally out this week in paperback.