I wrote this essay back in 2003 or so, when I had just gotten engaged and was living abroad in Italy for a month. (Later changed to a year.) This essay has never seen the light of day until now…

Christopher Nolan—and Wrist Watches

Two of the overhyped movies of the summer have been Indiana Jones and Dial of Destiny, and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer. Oppie’s huge, Indy’s a dud, at least that’s what the scuttlebutt says. Me, I loved seeing both of them, and it’s great seeing Harrison Ford back in action.

But let’s talk about watches…

I Write of Sherlock Everywhere...

I wrote two Sherlock-themed posts in the past year, devoted to the new Netflix series, Enola Holmes, based on the life of Sherlock’s youngest sibling, a teenager named Enola. Actress Millie Bobby Brown stars as the titular character, based on a series of books by the Edgar Award-winning writer, Nancy Springer.

Here’s why I think they’re wonderful movies…

Cool Software for Writers

Writers are always asking each other which software they use.

Do they write in Word? Pages? Scrivener?

Some writers swear by Word, for example. I hate the thing, and only use it to transmit a final document to editors or clients.

I wrote a few blog posts recently in which I delved into my current favorite apps for writers. I’m going to just quickly offer those links so you can find them easily…

My Forgotten Essay on Wood. Yes, wood.

I wrote this essay back in 2005 or so, after I returned from living abroad in Italy for a year. It’s never seen the light of day until now. Looking back, I see that that short time away changed the way I interact with the nature that surrounds my home today. I’ll offer some thoughts about that at the end of the piece. But first, the essay.

I remember the first time Italy taught me a thing or two about saving money. My wife and I rented a small country apartment last winter, just an hour north of Rome. The season had been unusually cold, windy and wet, and we spent a lot of time huddling indoors in front of the radiators or else shuttling in the car between tourist sites, restaurants, and shopping. One weekend, some friends arrived just as the weather took a break from the gloom, and we all pulled on our boots and hiked up the road to check out the view.

After about 20 minutes of trudging, we met a few women outside one of the big stone houses that lined the road. Three generations greeted us, nodding as we went past. Mama, daughter, and nonna. All were well-dressed, the nonna in an elegant silk scarf. They seemed ready for Sunday dinner, with one exception: each wielded a vicious-looking hand machete. At each woman’s feet was a stack of tiny freshly cut sticks of wood. Earlier in the week, one of the men who lived here had come by with chain saw and trimmed the trees lining the family’s driveway. Now, the women were finishing the job, deftly reducing the big branches to tidy bundles of kindling.

“Buon giorno,” we nodded.

For a moment the two cultures stood staring at each other before moving on.

“Buona passeggiata,” they said. Have a good walk.

“Buon lavoro,” we said. Enjoy your work.

The scene stuck in my mind all day. Those women had been dressed to the nines, maybe fresh from church, cheeks covered with sweat, hacking away like lunatics. The house behind them was huge and handsome. One of the men who lived here, I knew, was a local judge. Surely no one who lived here needed to cut firewood to stay warm. How wonderful, we thought. Somehow they couldn’t give up on such a quaint, rural tradition. Or so we thought.

The weeks rolled by, the weather turned warm, and one day our landlord presented me with a quarterly heating bill of $500. We balked. Gently, carefully, so as not to give offense, we politely insisted that that there had to be some mistake. How could hot water, heat, and running a stove amount to $170 a month for a two-bedroom apartment? The landlord, Erminio, admitted he was puzzled too. But he dutifully ran down and got some bills from prior years. We spent a little over a half hour poring over them. It was no mistake. He’d been paying as much or more for years, during the winter months when he and his family stayed in this apartment. Natural gas is insanely expensive in Italy, especially where it must be trucked to your home and pumped into your tank, as if filling a giant car that never budges. Want to save money? Chop wood. But Erminio was a busy man with a busy career, and he had no time to chop wood. And so he grimaced and paid up. And now it was our turn.

Once I understood this underlying economic reality, everything I saw happening around me became clear. Now I understood why my neighbors were such fastidious harvesters, cutters, and organizers of wood. I understood why I could hear Signor Basili’s table saw running every night for an hour before dinner, and why he seemed obsessed with filling his woodbin. I grasped why I spied immaculately stacked woodpiles everywhere, each neater than the last. I comprehended better why, on weekends when we drove past forests, the woods themselves looked so tidy: there was hardly a spare stick of wood lying around.

Denise making short work of an acacia tree in Italy, circa 2003.

After thunderstorms, entire embankments were picked clean like clockwork. When the state cut brush around local railroad tracks, workmen moved in with saws, buzzed the place down to the ground, and left it where it lay. In days, the locals swept in. Seniors with tiny hand saws. Weekend warriors with chainsaws, their BMWs parked by the side of the road, trunks stacked with cord wood and kindling. The occasional child following mom on the roadside, stuffing sticks into a plastic sack. Before long, the hillside was spotless, and the tiny tufts of new green sprouts signaled that the cycle was beginning anew.

What I had mistaken for a quaint, local predilection made good Euro dollars and sense.

I should say that all of these people have gas heat in their homes. Some are wealthier than the richest people you know. But they just choose not to use heat from the utility company. Granted, rural Lazio, just south of Tuscany, ain’t Alaska, but it gets cold on winter nights. Some days, when the heat wasn’t on, I saw my breath in front of my face indoors. The tips of my fingers were so cold I couldn’t type. I had been only too eager to crank up the heat, but my neighbors never fell prey to such thinking. Damned if they were going to pay when they could heat their homes or cook their food for free, all for the price of a few calories.

In this neighborhood, wood is money. Collecting and managing wood is good exercise, too, but people here would scoff if you brought that up. In winter, when the fields are empty and work slows down, my neighbors carry ladders out to each of their trees and prune them back severely. The branches go in the wood pile, and the trees’ trunks grow thicker, stronger, clubbier with each passing season, impervious to storms. Also in winter, people clip the tall reeds that grow in marshy ditches, and dry them for summer, when they use them as fence posts and tomato stakes and shade awnings. They snip the whip-like branches of the vimini, or wicker tree, soak them in water, and use them like twine to tie everything from grapevines to cucumber plants to even more bundles of wood. All summer or winter long, you can smell wood burning in the distance, meat grilling and pizzas baking over wood coals. More than any other, that delicious fragrance is the quintessential smell of Italy.

Not long after I paid for that heating bill, I returned for a visit to my hometown in New Jersey, where my parents still live. Tooling around suburbia, I saw with new eyes the place where I’d grown up. I saw untended trees everywhere; people don’t bother to intervene in their growth. Consequently, huge, fragile limbs dangled over roadways, wreaking havoc when they fell in storms. When that happened, sanitation crews came out, cut it all up, and hauled the lumber away.

Because the wood = money equation had never been drummed into their heads, my American neighbors spent money on combustible products that would have been rendered unnecessary if they simply used what grew from the earth. Free lumber went to the municipal dump, and they bought charcoal and propane tanks at the big box stores to grill their food. In fireplaces they burned synthetic logs impregnated with chemicals. Landscapers hauled away weeds. Kitchen scraps went into the trash. And gardeners bought manure, topsoil, and bags of compost for the garden. People ordered tomato cages from garden catalogs when they could use branches from the same trees which sorely needed pruning. They bought $5 bottles of dried herbs at the supermarket when a couple of perennial plants from the nursery would grow forever in their yard and give them decades of flavorful leaves for free.

Don’t get me wrong. There is nothing wrong or bad or stupid or dumb about any of this. In one culture, people had simply been trained to believe that what grew in their backyard was trash. All those branches, all those sticks, all that nature was an annual hassle that had to be collected and flung away. Powerful market forces had persuaded them if they wanted to use their fireplace, cook their food, or have a nice garden, then they had to spend money. It was a different world than the one I had seen. I wasn’t in Italy anymore. I was in America.

Almost 20 years have passed since that time away. Have we really put that much into practice? Sort of!

A fallen 90-foot pine in my backyard, circa 2022.

All our kitchen scraps and most vegetation that is not invasive goes into a compost tumbler. In fact, we’re on our fourth compost station since we started living in North Carolina. I’ve become an inveterate collector of sticks that fall from our trees, and any time I hire a tree service to take down a damaged specimen, the trunks and limbs are either ground to mulch on site, or cut into movable chunks that I use to line the trails behind my house. We burn wood in winter and fall in an outdoor fire pit. We have also cooked on that pit. (I don’t have a propane grill, but do have a wood-burning outdoor oven.) We grow a variety of herbs and flowers that are dried in a dehydrator for use off-season. We make lavender sachets to give to friends, who seem to like them. (They do keep moths from destroying your clothes!) If the woodpile (shown above), runs low, I buy cordwood from various locals who support themselves hauling and cutting wood. My house is heated by gas, so I can’t claim to have severed myself from the teat of the power company. But about half of my electricity at this point comes from the sun.

If you had asked me in the 1990s, when I was living in the New York area, if this was the life I envisioned for myself, I would have scoffed. But the signs were there. In the first apartment I ever owned in Hoboken, New Jersey, my downstairs neighbor—a Wall Street guy—had access to a yard that he never used, and allowed me to keep a small garden and tuck a compost tumbler under the apartment building’s fire escape. I grew tomatoes, lavender, and sunflowers, which his girlfriends seemed enjoy on weekends when they ventured outside.

A Eulogy for My Father

Since I wasn’t able to attend my father’s funeral in the Summer of 2022, due to my cancer diagnosis and imminent treatment schedule, I did the next best thing. I wrote a eulogy for my brother to deliver at the service. The following piece is the one my brother delivered. I think it’s filled with some hilarious anecdotes that would appeal to all readers, even ones who didn’t grow up in our family…

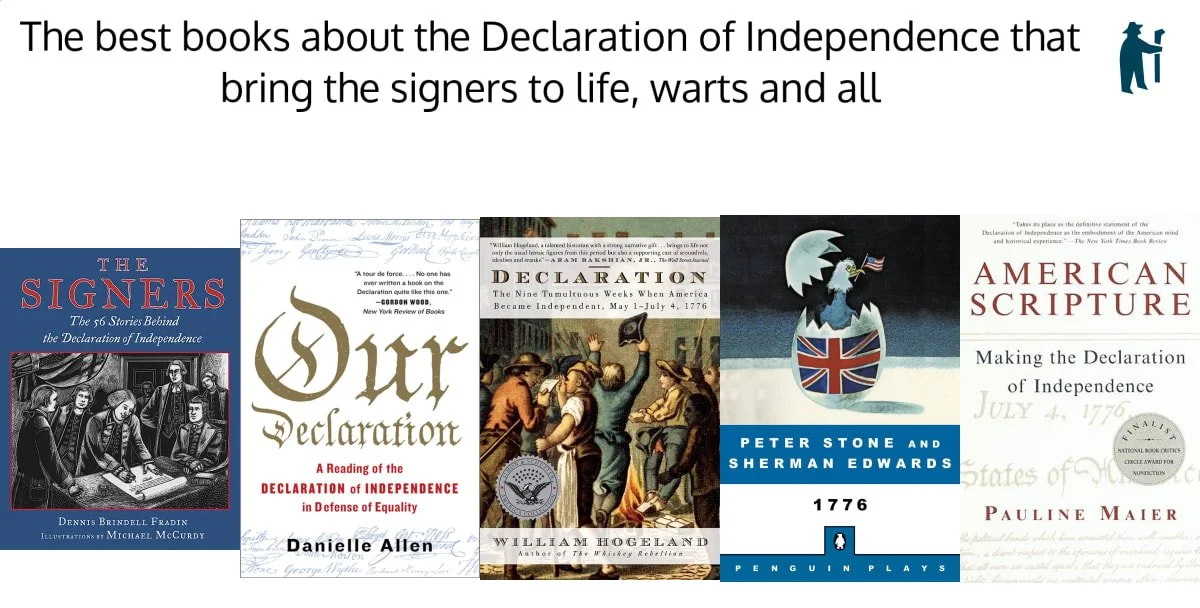

Best Books on the Declaration of Independence

I promised to share my new list on Shepherd.com, the book recommendation site, as soon as it was up. The folks over there got it up pretty quick.

You can check out the new list right here:

The best books about the Declaration of Independence that bring the signers to life, warts and all

That brings my number of book lists on Shepherd to four. Besides the new one, the others are:

Best Books about the Creation of the U.S. Constitution.

Best Books for Discovering Italian Mystery Novels

Best Books for Helping Your Kid Fall in Love with Math

My wife has contributed three lists:

Best Books on or by Maverick Women

Best Books on Writing (from a NY Times Bestseller)

Best Books on the Manhattan Project and the Making of the Atomic Bomb

You might be wondering: Dude, why are you doing these lists? Shouldn’t you, like, be writing?

Good questions.

The easy answer is, writing these lists for Shepherd help my books reach a wider audience. There’s an acknowledged issue with recommendation engines on many sites. You buy a case of ham, and the damn engine keeps recommending the same fucking brand of ham to you, albeit in different size ham cans, even though you are now in the market for a giant wheel of Parmigiana. Or water shoes. Or a life raft.

It’s smarter to get recommendations from a live human being. And when it comes to books, authors know a lot about books—which to read, which to ignore, which really make a difference. So as long as Shepherd allows me to pitch lists to them, I will. I go through a lot of books in my life, and it’s good to pass that knowledge on to someone.

Photo of the National Archives building (above) by me; bobblehead video also, sadly, by me.

My Double Whammy

A year ago today, I got blindsided by life.

My wife was in London on a trip in service to one of the nonprofits she volunteers for. The two of us were speaking via WhatsApp, when another call came through on my phone.

“Gotta go,” I said. “It’s the doctor.”

“Go!”

This was the call we were dreading, but still quite anxious to take. A few months ago, I’d spotted a lump under my jaw while shaving. As a writer, I’ve perfected the arts of avoidance and procrastination. I did my best to ignore the lump. After all, I had a physical coming up, I told myself. I’d mention it to my doctor then, a date which was three months in the future. That physical led to a battery of subsequent tests. And here on the line was my ear, nose, and throat specialist.

“It’s cancer,” he told me. “We don’t know what type yet, but I’m gonna make a referral. Get the ball rolling. You’re going to hear from the radiation oncologist within the next two days. Just sit tight. In a little while we’ll know exactly what kind it is.”

Here’s a piece of advice. Don’t Google head and neck cancer. Just don’t. The images are terrifying, and there are far too many different forms of cancer to be speculating about each without hard evidence.

All I knew at the moment was that I had cancer. But life wasn’t done with me yet. I hung up the phone intending to call Denise. But another call came through, this time from my brother in California.

“Dad’s gone, Joe,” he said. “It just happened.”

My father had entered the hospital the previous Friday after one of his home care workers found him sitting in bed complaining of a headache. He had trouble standing. At 91, Dad had a litany of health issues but he’d managed to bounce back for decades. He came from a long line of people who had miraculously lived into their nineties. His brother died at 92, his mother at 95, his aunt at 100, his uncle at 103. I’d last seen my father in June, and he still had all his marbles.

That all ended Friday. He needed immediate surgery for a brain bleed. That procedure went well, supposedly, but he hadn’t woken up post-op, as his doctors had wanted him to. At that age, if he didn’t immediately wake he never would. They recommended we take him off life support. We agreed. I was prepared for it. My brother asked if I wanted to speak to him before they did, but I said no. It felt like a foolish gesture for a guy in North Carolina to mouth words into a phone to a man lying in a bed in California in a virtual coma. I had just seen him a month ago! I struggled to remember: when we parted, had I told him how much I loved him?

I phoned Denise. “It is cancer,” I said, “and my father died.”

“Wait, what?” she said. “When did that happen?”

“Just now. My brother called.”

“We were off the phone five minutes!”

Well, sometimes it only takes five minutes for shit to go sideways.

Since then, my life has been on hold. The cancer turned out to be HPV-positive, which is eminently treatable; the chances of recurrence post treatment is less than five percent. Still, no one wants to wake up in the morning with only two things on their to-do list:

1. Get chemo

2. Blast face with gamma rays.

All the plans we had for the rest of the year evaporated. Naturally, I could not attend my father’s funeral because I now had a flurry of pressing medical appointments. That was crushing and painful. I used that time to hastily wrap up all current projects. I wrote a slew of articles for SleuthSayers, the mystery writers blog I write for, and scheduled them so there would be no interruption in my presence there. I submitted the book I was ghostwriting to my clients for review. Commitments honored, I proceeded to drop the ball on everything else. The garden went to crap. Receipts piled up. This blog and website went dormant. Short story ideas and personal book projects dried up. Any time I managed to get to the mailbox, I found a half dozen more fat envelopes with hospital bills and statements from the insurance company. They piled up too.

It’s been a year. The treatment’s over, as is the rehab, such as it was. I’m still quite scrawny, having lost 45 pounds and gained back half, mostly in the form of pasty white fat.

I’m just getting around to picking up the pieces. I’m told that somewhere under the detritus of my office lies my desk. I’ll let you know if I find it. That said, in the next few months I hope to be more present here. Tidy the place up. Post more often. Think. Write. Play the mother of all catch-ups.

Please don’t say you’re sorry for me. because I know you are. Hey, I’m one of the lucky ones. I still have my tongue, larynx, and pharynx. I’ll have a sexy, gravelly voice and live with dry mouth—and lozenges and gallons of drinking water and incessant peeing—for the rest of my life. Small price to pay. It could have been worse but wasn’t, for which I’m so, so grateful.

Just do me three favors: First, love those whom you love—loudly. If you have kids, get them the HPV vaccine. And if you find a lump, get it checked out. Like, now.

Image by Joshua Earle @ Unsplash

Best Christmas Cocktail Books

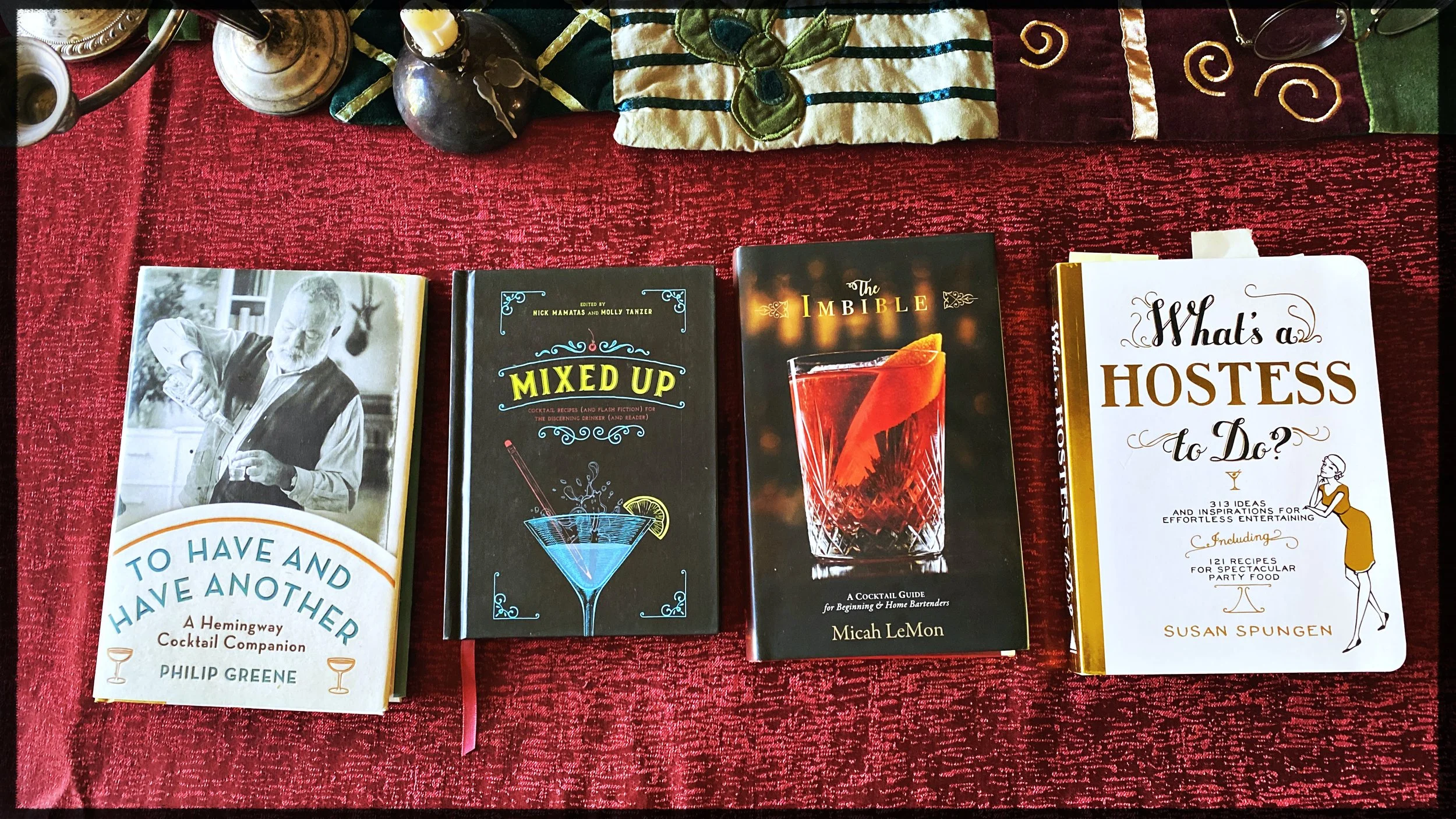

We have a little stash of cocktail/mixology books that get a workout every year in December. One year I shared my top four favorite books over at SleuthSayers, in a post entitled A Serious Case of Libations.

If you want to cut to the chase, visit that post immediately.

If you don’t like clicking over, let me make this painless. If you’re one of those people who hates planning parties because you never know what to buy, what food and drinks to set out for guests, and how much is too much, or worse, too little, then the book you need is the first one on my list.

What’s a Hostess to Do? by Susan Spungen. Why this book? Because Spungen is a freaking expert, a former food editor at Martha’s magazine. She teaches you the difference between a dinner party and a cocktail hour, and she spells out exactly what sort of menu you need to lay out for each. I hate thinking abut this stuff. But with this book in hand, suddenly I look like the second coming of the Galloping Gourmet. So get this first, mostly for the food, the recipes, and the logic. Yes, she talks about booze and how much you need to buy, but so much more. And if you’re a big hairy macho dude who thinks the title is too girly, write me and I’ll mail you a Sharpie.

The Imbible: A Cocktail Guide for Beginning and Home Bartenders, by Micah LeMon. I know the author. He’s a real bartender and mixologist. This book is as beautiful as the drinks he makes. It’s a little hard to find, but it’s a really lovely book, kind of like a small coffee table book with gorgeous photos. You won’t find mixer drinks in here (such as gin and tonics) because they are frankly too easy to make. It’s also a great gift book because it’s so damn attractive. Lots of photos showing such things as what kind of glassware to buy, what tools, and how to make perfect ice cubes.

To Have and Have Another: A Hemingway Cocktail Companion, by Philip Greene. Now we get to the literary books. This one is focused almost exclusively on the world of Erenst Hemingway—his books, his real-life settings, the actors and directors who brought those books to life on the big screen, and the sexy man-drinks that emanated from his typewriter. Yes, there are recipes, but there are also movie stills and photos of Bogey. If you have a writer friend who digs that world, this is the book to get them.

Mixed Up: Cocktail Recipes (and Flash Fiction) for the Discerning Drinker (and Reader), edited by Nick Mamatas and Molly Tanzer. Another literary book, but this one is packed with actual literature. The editors asked a bunch of writers to write short stories that each feature a cocktail. So you read the story, and then you get the recipe for how to make the drink. Clever idea, and the stories are equally so. This is a great gift for writer friends too. The stories are all flash fiction, which means you’ll down them quicker than the bevs.

Okay, those are the books I mentioned in my original post, but readers and my fellow bloggers also had ideas on the subject, so I’ll add a two of those.

The Hour: A Cocktail Manifesto, by Bernard DeVoto. The author was a Pulitzer Prize-wining historian who really knew his cocktails. The original book was pubbed in 1951, but has been lovingly recreated for modern audiences. The prose is somewhat mannered and restrained tongue-in-cheek, as if anyone who drinks cocktails will be appropriate after knocking back a few. Definitely for friends who enjoy three- and four-syllable words.

The Deluxe Savoy Cocktail Book, by Henry Craddock. This is another historic text, pubbed in the 1930s in the UK. The author was an acclaimed mixologist who shared 750-plus drink recipes for newbies. You can find many versions of this book on the market. Get the cheaper one if you think you’ll spill angostura bitters all over it; save the nicer one for gifts.

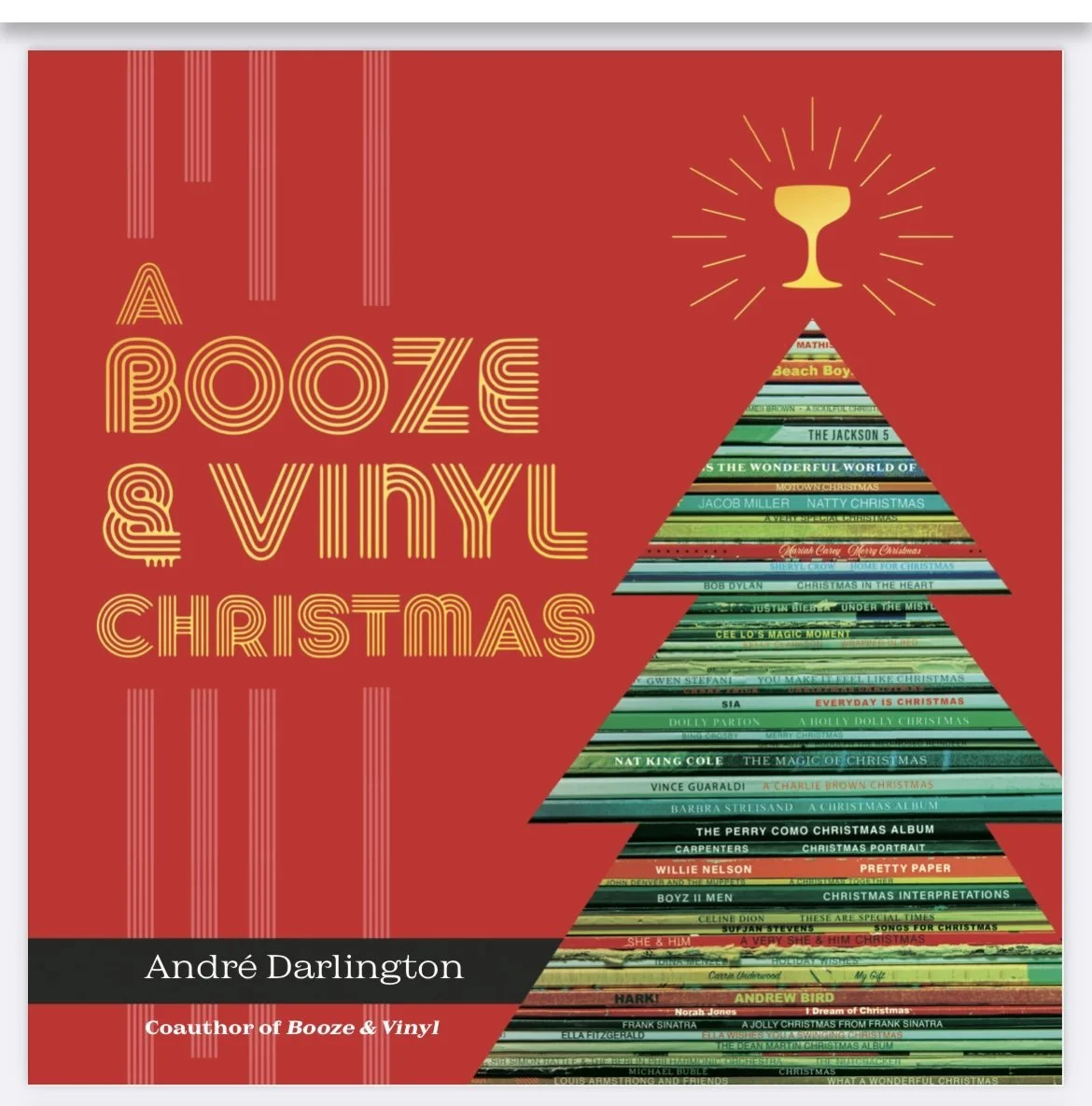

Later this year, I discovered another marvelous book that I simply had to add to this list:

A Booze & Vinyl Christmas, by André Darlington. Lots of writers write about cocktails, but Darlington is the master, with 10 books to his credit. This one is the third in his Booze & Vinyl series, and grows out of his past as nightlife journalist, restaurateur, and DJ. He literally only focuses on vinyl, so if a Christmas album never appeared in that format, it’s not featured in this book. That allows him to dream up magnificent scenarios during which you can listen to, say, the A or B side of an album, drink one of his wonderful cocktails, and get your tree decorated, hide your pickle, write your Christmas cards, and so on. He includes wonderful light snacks along the way as well, and behind-the-scene stories about the songs and albums. Best of all, it’s a beautiful book with great photography. It’s my new favorite book to gift hosts when I arrive at their home for a Christmas party.

There you go—all the ones I have personally used and enjoyed.

I’ll leave you with one promise: The modern world of mixology owes a huge debt to two men, Harry Johnson and Jerry Thomas, who were bartenders in the 19th century. Both wrote bartenders’ manuals, which have entered the public domain and are often cheaply reissued. I’m trying to find which editions of their work is the best. When I do I will add them to this post in the future. Enjoy then, drink up!

Photo above by little ol’ me. (And no, that monstrosity is not in any of these books, thank God.)